The wind power industry has long faced a bit of a frustrating problem. Gigantic blades are more efficient, but they’re also hard to ship. A single blade can be more than a few hundred feet long, and they’re a logistical nightmare to haul down roads and load onto barges to get to their destination turbines. Startup company Radia thinks it has the answer. For the past decade, it has been developing an aircraft of mammoth proportions that would dwarf even the iconic Antonov An-225 Mriya. The WindRunner is huge, goofy, and I hope it becomes a reality.

The world of super-large aircraft has been a much sadder one since 2022. Early that year, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine resulted in the destruction of the sole operational Antonov An-225 in the world. The distinctive Antonov and its sextet of engines had wowed the public for decades and carried the biggest loads that no other plane could haul. Antonov has vowed to rebuild the world’s largest plane, but when it does, the An-225 may no longer hold the crown.

Since then, other planes have been wrangling for the coveted position of “biggest flying object on the planet.” The dual fuselage Scaled Composites 351 Stratolaunch is shorter than a Boeing 747-800 at 238 feet, but its 385-foot wings make it the largest plane in the world by wingspan. Of course, there are also legends like the Airbus A380, the world’s largest passenger aircraft, and the Boeing 747, the Queen of big passenger jets until the A380 arrived at the terminal.

Here’s the Antonov if you’ve forgotten what that beauty looks like:

If the folks at Radia succeed in the construction of the WindRunner, they’ll take the record of the world’s largest aircraft. This beast would be about 100 feet longer than a Boeing 747-800 and still 81 feet longer than the late Antonov An-225. Supposedly, the absolute unit of a plane will also have 12 times the cargo volume of a 747 and the ability to operate at unpaved airstrips.

So, is this thing the real deal? The New York Times recently covered the plane, and that’s how it got my attention. Seemingly, everyone’s been talking about the WindRunner, regardless of whether their publication has a transportation angle or not.

Aviation For Wind Energy

Radia is the brainchild of aerospace engineer and serial entrepreneur Mark Lundstrom. He founded Radia in Colorado in 2016 to explore the intersection of aerospace and energy to find a profitable way to reduce carbon emissions. Here’s the story of Radia from Lundstrom:

Shortly after Radia was founded, a press release came out from two wind turbine manufacturers that compete for every deal globally. They were frustrated that the energy industry knows how to make offshore-sized turbines and deploy them in places like the North Sea but can’t take that knowledge to deploy them onshore where the market is an order of magnitude larger. Their release asked if an aerospace company, engineer, or entrepreneur could help them figure out how to airlift an object that weighs 45 tons and is over 100 meters in length, and land it on a piece of dirt in the middle of a wind farm. I showed up within a week and started working with them. Our massive cargo aircraft WindRunner is our solution to the problem as it can deliver offshore-sized blades onshore and enable what we call GigaWind.

Lundstrom is joined by a large team of aircraft engineers and other engineers from the energy sector.

Radia has a pretty huge marketing push behind its business. The United States Department of Energy projects that by 2050, wind power will have a capacity of 404.25 GW across 48 states. This is compared to a capacity of 113.43 GW in 36 states in 2020. Wind turbine production is only expected to grow.

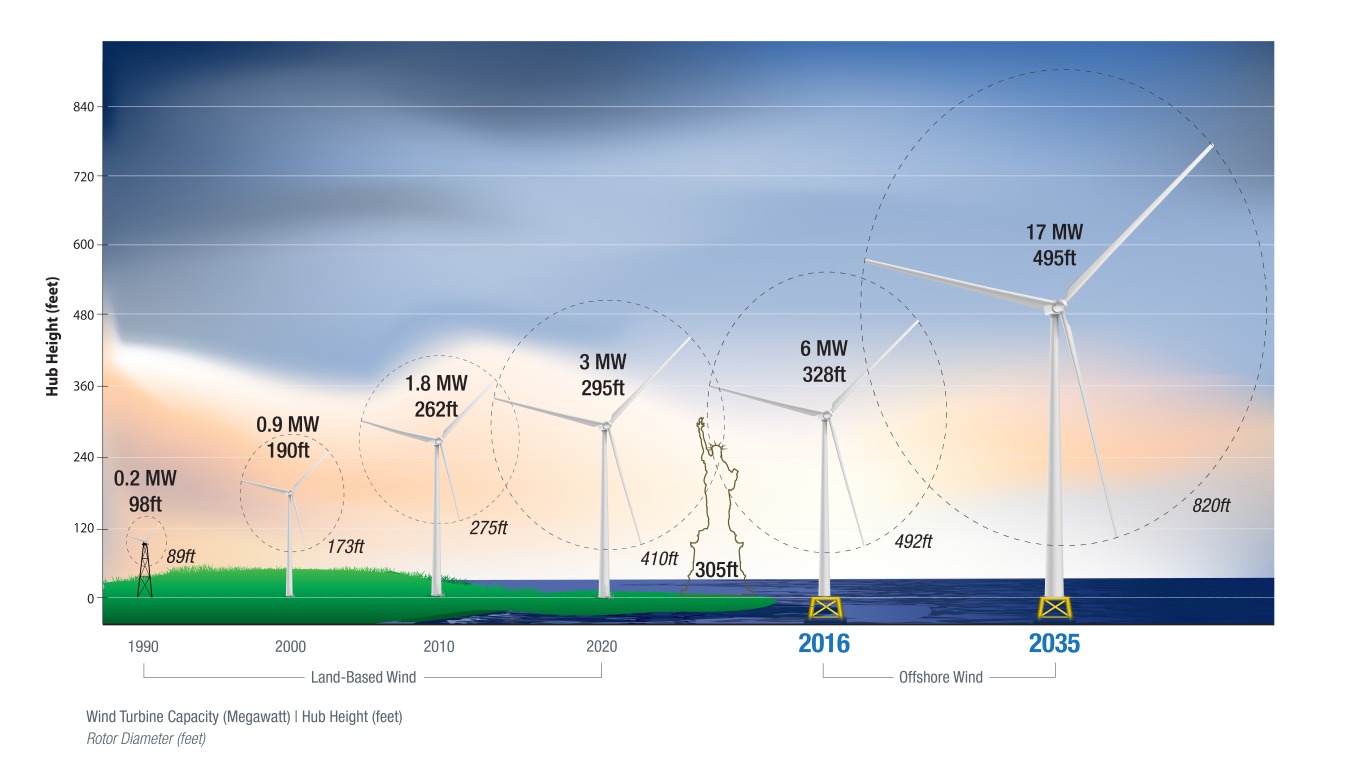

Generally speaking, larger wind turbines with longer blades are more efficient turbines. In short, this is because longer blades have larger swept areas and can capture more wind. So companies are constructing absolute monsters of turbines with blades over 200 feet long. As of 2024, the world’s largest onshore turbine blade, for the SANY SY1310A, is 430 feet long.

Radia claims that infrastructure is limiting the size of most other turbine blades for onshore applications. The company claims that most road infrastructure struggles with blades stretching 230 feet long. Further, the company says, super large blades have quite a huge diameter, which means that shipping a blade by road would require some clever navigation to avoid obstacles like overpasses. This is why some of the biggest wind turbines that you’ll find will be offshore.

As NewScientist reports, the general idea is that the larger you can make a turbine, the fewer of them you’ll need to reach a given capacity. However, as the publication reports, there are tradeoffs. Consider that, when it’s running, the SANY SY1310A’s blades cover an area of over 800 feet. Of course, then you have to figure out what to do with the structure after its service life ends. All of that aside, NewScientist notes, you still have to figure out how the heck you’re getting those giant blades to a wind farm in the first place.

So, to repeat myself here, Radia’s logic is that land transportation limits the size of onshore turbines, so what if the company took the hassle out of shipping turbine blades? Instead of navigating a blade through tight streets, you just load it onto a plane and fly it directly to a farm. Radia’s plane would permit the shipping of larger blades for onshore developments and thus pave the way for the creation of the biggest turbines and wind farms. This concept is what Radia calls GigaWind.

To be clear, Radia will not build turbines or even blades. The whole idea is that the plane will allow other companies to install the biggest wind farms. The GigaWind thing, which is included in the marketing of the WindRunner, is somewhat confusing since it’s not a product or service that will be offered by Radia.

The WindRunner

Radia’s project is the WindRunner plane. In 2024, here’s what Radia said about the aircraft:

Radia’s WindRunner aircraft, capable of landing on short, semi-prepared runways including those made of packed dirt, will be purpose-built to deliver these large blades and other components directly to onshore wind farm sites – greatly expanding the number of locations available for large turbines and enabling onshore wind to scale. Opportunities include reducing transmission costs and increasing reliability by building wind energy sites closer to demand, creating hybrid wind/solar sites to produce clean power around the clock and throughout the year, and generating the large amounts of clean electricity needed to produce green hydrogen.

The innovative design of WindRunner only requires a 6,000-foot semi-prepared dirt or gravel landing strip at a wind farm to deliver its payload. This also enables it to land at almost any commercial airport around the world. WindRunner will be 356 feet long and its volume is 12 times that of a 747, and an overall length of 356 feet to carry the largest payloads ever moved by air.

Radia plans to produce a fleet of certified aircraft at Radia’s U.S. assembly site. WindRunner is more than halfway through the time required to design, build and certify an aircraft.

Radia says that the WindRunner will have a range of 1,200 miles and cruise at 41,000 feet at Mach 0.6. Further, Radia says that the fuselage, which is designed like a Boeing 747 where the flight deck sits in a pod above the main deck, will have 272,000 cubic feet of cargo volume and a payload capacity of 160,000 pounds. The cargo inside could be as long as 344 long, 24 feet tall, and 24 feet wide. Those wings look sort of stubby because they sort of are compared to the fuselage length. The fuselage is 356 feet, and the wingspan is 261 feet.

The WindRunner is projected to be a big bird for sure, but what about that claim of having 12 times the cargo volume of a Boeing 747? Well, cargo airline Cargolux says that its 747-800F aircraft, the final edition of the 747 Freighter, has a main deck with 24,462 cubic feet of space. Times that by 12 and you get 293,544 cubic feet, or more space than the 272,000 cubic feet claimed by Radia.

Cargolux also runs the older and smaller 747-400F, which has a main hold carrying 21,645 cubic feet of cargo. Times that by 12 and you get 259,740 cubic feet, or less than what Radia claims.

In case you’re curious, the Boeing 747-400 Large Cargo Freighter, also known as the Dreamlifter, has a hold carrying 65,000 cubic feet of Dreamliner parts. Cargo volume goes up significantly as you make a fuselage taller, wider, and longer.

Another massive aircraft is the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy, and the Radia would dwarf its 31,000 cubic foot capacity:

Regardless of whatever Radia used as a base unit for the 12 times claim, Radia’s claim of getting 272,000 cubic feet out of a giant 344-foot hold seems to be achievable. What’s interesting is the specification that the gigantic WindRunner will carry only 160,000 pounds. A Boeing 747-400F can carry around 249,000 pounds, and the bigger -800F hauls 295,000 pounds. The Antonov An-225 carried a whopping 550,000 pounds when it was still in one piece.

However, the low carrying capacity of the WindRunner is probably because of its specific mission to carry wind turbine blades. Still, one of Radia’s goals is to make a ton of money, so it seems like a missed opportunity that the WindRunner won’t be able to carry cargo as heavy as existing freighters can haul. The U.S. military is looking into the feasibility of using WindRunners to carry fighter jets, so maybe that whole money thing won’t be a problem.

At the same time, the projected lighter weight of the aircraft may help it with its other statistic: The takeoff roll. A fully loaded Boeing 747-800F may take 10,465 feet or so to take off. The Radia, which will be significantly longer than the 747-800, is said to be able to lift off the ground from an unpaved airstrip in only 6,000 feet. I would pay money to see something the length of this thing manage to leave terra firma in just over a mile.

Presumably, this also means that the Radia will have some sort of hot rod engines under its high wings. Unfortunately, Radia hasn’t said anything about installed power. As you’ve probably already noticed by now, Radia has also issued only renders of the aircraft. That being said, Radia said that it’s not trying to reinvent the wheel here. It’s said that the plane will be built with conventional methods and technologies. The “innovation” is just that the plane will be extraordinarily huge.

Maybe You’ll See One Someday?

Radia sees a market for a whole fleet of WindRunners. These won’t be flying regular cargo, but the expectation is that the wind turbine industry will become so huge that just one aircraft won’t do.

Radia says that it’ll officially unveil the WindRunner at the Paris Air Show next week. Then, the company hopes to have at least one of these birds in the sky by the end of the decade.

It seems like what Radia is proposing here is theoretically possible. It sounds like something this huge has no business getting off the ground, but that’s also what some people said about greats like the Airbus A380 and the Boeing 747. I’m skeptical, but maybe I’ll be proven wrong. Will Radia go into the history books as a record-breaker? It’s too early to tell, but you bet I’m going to be watching.

The post A Company Wants To Build A Humongous Plane 100 Feet Longer Than A Boeing 747 With 12 Times The Cargo Space, And For A Very Specific Reason appeared first on The Autopian.